Goodbye Slobo. Hello Grandmaster Flash.

BY Nathan Gilbert, August 28, 2009

(Photo Credits : Nathan Gilbert)

“Exit out of ten years of madness.”

This slogan, a direct reference to Slobodan Miloševic’s autocratic reign over Serbia, was the message behind the first Exit music festival. Held then on the banks of the Danube River in Novi Sad, Serbia, the event is now in its tenth year and has grown to become one of the world’s biggest and most popular festivals, attracting thousands of people from all over the world.

Exit started as a form of political dissent in the summer of 2000, following a decade of ethnic conflicts, wars, nationalism, and xenophobia within the countries of the former Yugoslav Republic. For 100 days, thousands of youth, primarily from Novi Sad and the Vojvodina region of Northern Serbia, took to the beach along the Danube River equipped with music to protest the brutal repression and censorship imposed by the Milošević regime which kept Serbia closed to the world. Fueled by political activism and a desire for change, the festival culminated in a huge “get out the vote” campaign preceding presidential elections that helped bring down Milošević’s reign. The following year Milosevic was arrested for war crimes by the United Nations’ International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Even though much has changed in this part of the world since then, the desire for openness and political progression remains at Exit’s core. The festival continues to highlight various social causes to encourage awareness and action every year. This year launched a Green and Clean campaign in an effort to promote environmental messages and to join other European environmentally friendly festivals.

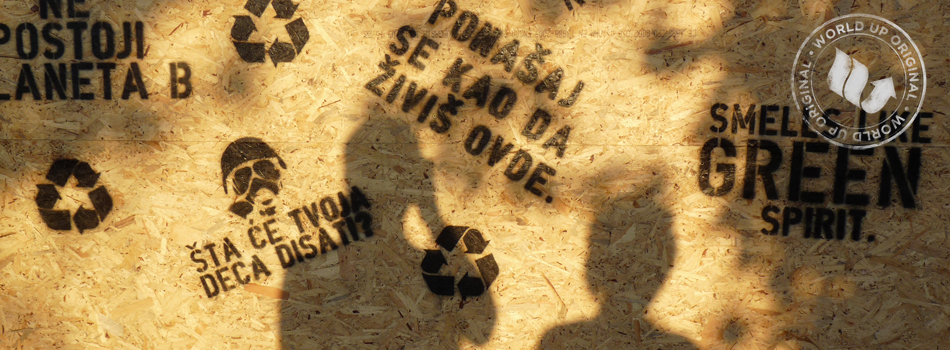

When I attended, I was able to take part in the Green Guerrilla campaign, which encouraged environmental youth activism. Each night before the performances began a group of about 15 to 20 Serbian youth took part in volunteer and activism training, discussions on environmental issues, and community awareness techniques. Green actions, including the creation of graffiti stencils for environmental messages, recycling, sorting waste, and public awareness campaigns, were staged all over the festival and campgrounds.

Natalija Simovic, a frequent Exit-goer, described her first experience at the event: “This one brings back memories. I was 17 when I was at [the] first Exit festival and I remember I was enormously grateful for the fact that foreign artists [were] finally playing in Serbia, and that in this sense we are opening up to the world.” Natalija said that Exit’s influence goes far beyond that of a regular concert or music festival. “I am sure it represented a lot to Serbian youth,” she said, “because it was in a way announcing some better times, a perfect celebration of liberation from Milošević’s regime.”

Following the first year of Exit, the festival moved across the river to a larger venue, Petrovaradin Fortress. The historic site garners popularity among festival-goers and the big names that play there, alike. Once inside the Fortress walls, spectators can wander around the grounds to explore the many different stages, some in the moats and others hidden behind long tunnels. At the festival one is constantly surrounded by a diverse group of people speaking various languages, music spanning the genres, and history dating back hundreds of years. It helps make the festival unmistakably unique.

An extensive number of artists come to Exit each year. While big names like Grandmaster Flash, Lily Allen, Patti Smith, Moby, Kraftwerk, Arctic Monkeys, Korn, and Prodigy (all from this year’s festival), grace the main stage, there are also smaller stages scattered throughout the fortress to showcase music from all over the world. One stage that has given Exit international fame is the Dance Arena, where top DJs and thousands of fans party until early morning.

As a somewhat seasoned festival-goer, I must say Exit is like no other. The festival is not only about coming to party and see your favorite artists; it’s also an opportunity to interact with your regional and global neighbors. There is less protest now, but music continues to be the catalyst that provides youth a voice, a message, and a tool for change. As Serbia and neighboring countries emerge from the previous decade of war and conflict, Exit has become a beacon of global exchange of ideas, music, and passion for social change. It has given youth in the region an outlet to perhaps reconcile and rebuild using music as a social magnet.

Ten years after Exit began, the festival has grown immensely. With rapid commercialization, Exit certainly is no longer what it was when it first began as a form of expressing dissatisfaction with the sociopolitical situation in Serbia. Natalija told me, “Nowadays ask any young person from Serbia about Exit and there is a big chance they will tell you it ‘turned into a festival for Brits.’” It’s true, there were probably about 10,000 British youth at the last festival, who came for nothing more than a pocket-friendly five-day party. But in many ways Exit has always been a form of escape, a party—and a protest. As Bojan Boskovic, one of the founders of Exit, told the BBC, “We have a balance between politics, social issues and music. We will never lose that.”

A brief trailer for a documentary being made on the Exit Festival:

A brief interview piece with a variety of artists, NGO representatives, and festival goers including Afrika Bambaata and the Hives:

Permalink:

No comments yet.